Downers Grove Chiropractor Talks Leg Length

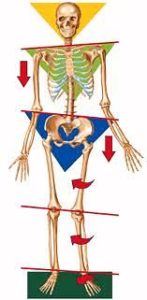

Traditional biomechanical view of the human body

As long as Downers Grove chiropractors, bone setters, massage therapists, physios, and other forms of manual therapists who deal with the musculoskeletal system have been around they have often found structural issues to be a root cause of a patients pain or injury. These issues range from bones being out of place (the infamous subluxation), to muscles that are “turned off”, to a hyperdominant random muscle (that darn quadratus lumborum).

This post is about a common “problem” that is often labeled as the reason humans suffer from problems ranging anywhere from low back pain, headaches, to pain in the big toe...leg length inequalities (LLI).

Without any context and a tunnel vision geared towards the biomechanical view of the body, LLI might sound like a logical reason you might be experiencing pain. If one leg is longer than the other, it could throw your body off balance, cause you to walk in circles, putting more forces in one area eventually leading to pain. It turns out this is an overly simplistic view of the body and completely disregards the human bodies ability to adapt, something which it has been doing for, you know, millions and millions of years.

If we are going to have any long term success in treating pain in humans we must have a deeper understanding of what pain is. I have written in a bit more detail HERE, but in short, the current best understanding of pain is viewed under the lens of the biopsychosocial model, which states there are many confounding factors that contribute to a human’s pain and blaming it on one source, be it a structural, social, or psychological issue is incredibly short-sighted. Many factors contribute to the genesis of pain and only addressing one aspect of it does a disservice to our patients, especially when we are blaming something as nuanced as pain on something as ubiquitous as a leg length discrepancy.

LLIs can be divided into two separate categories, structural & functional, and it’s important to differentiate the two because one potentially matters and one likely doesn’t.

Structural LLIs are when there is a legitimate difference in length somewhere along the structure of the leg. This can commonly be in bones such as the femur or tibia, the two bones which contribute to the majority of leg length. This difference can happen from injuries, surgical alterations, birth anomalies, etc. These differences in structural LLI tend to be the larger of the two categories and are more commonly clinically significant once they reach a certain difference, which tends to be around a 20mm difference in leg length, but in truth, this is a minority of cases.

In comparison, functional LLI are inequalities due to postural compensations in the body. These functional LLIs are commonly blamed on over-pronation of the foot, hip rotations, tight muscles or inhibited muscles, not enough qi, or not properly bracing your core 100% of the time during all activities. Clinicians will tell you that once these issues are fixed, then your legs will be back to equal, your pain will disappear, and maybe even your performance will increase in whatever sporting activity you partake in. I find myself saying this over and over again, if only it were that simple our jobs as clinicians would be much easier.

If we are going to blame pain and injury on a structural factor, we need to observe it’s prevalence in asymptomatic populations, as in how common is said structural “abnormality” in people who have zero complaints. As far as structural variations go, LLI is by far one of the most common in the human body. Multiple studies have estimated that LLI are prevalent in ~90% of the human population with an average of 5.2mm difference in leg length and the right leg being the more common of the two. When I was in grad school I was always amazed at the professors and clinicians who “predicted” a patient or a student had a LLI. Turns out if you throw a stone in the ocean you are going to hit water. Let’s think about that for a second, if LLI is a cause of low back, hip, knee, ankle, or foot pain like so many clinicians claim, 1) why doesn’t 90% of the worlds population live in chronic pain and 2) why doesn’t 90% of the population have injuries stemming from their LLI?

The answer is because the vast majority of people have a LLI that is clinically insignificant, an average of around 5.2mm. This discrepancy is likely an adaptation to the gravitational forces humans experience every single day and nothing more than that. It doesn’t mean the someone is pronating too much. It doesn’t mean people’s hips are off balance and needed to be fixed. It’s not from a tight QL yanking up the pelvis. It’s definitely no reason to sign up for 3 visits a week for 12 weeks to avoid future arthritis and joint degeneration (which is going to happen anyway). In the vast majority of cases blaming pain on LLI is a made up problem that doesn’t exist and is a way to convince patients who don’t know any better they need x or y treatment to be fixed.

As for those of you who have been told you have a LLI (which you probably do and it probably doesn’t mean much), had an adjustment and BOOM you feel better there are a few answers that could explain your reduction in symptoms. The first and foremost is the hallowed placebo effect, something which has been playing a role in the reduction of symptoms since the beginning of time. If someone is given a problem and the problem is perceived to be fixed, symptom reduction is likely to happen. Consider the scenario when we fell and bumped our knee as a child. Mommy comes and kisses the boo-boo and the knee feels better. Does mommy’s kiss have magical healing powers that restored the tissue and healed the injury? No. That is a prime example of the placebo effect working at its finest.

Translate to the scenario when a patient is told their legs are different lengths and the only cure to their problem is a form of manual therapy to restore balance. Patients may feel better after treatment, but how are we sure that it is that specific treatment itself that causes the reduction in symptoms? This brings up the idea of the post-hoc fallacy, which describes a scenario where event y follows event x, therefore x causes y. Consider this, the mailman comes to your door every day. Your coonhound also barks at the mailman when he approaches your door every day. After the mailman drops off the mail he leaves and goes to the next home to drop off the mail. Does he leave because the dog was barking at him or for another reason?

In the context of treating a LLI, does the reduction in symptoms occur due to the specific clinical intervention, a regression to the mean, or the unknown? Was it the “balancing of structures” or the “releasing of tissues” or was it the placebo effect? If the initial “problem” was likely not even a concern to begin with (in the case of an average LLI), the unknown is by far the more likely answer.

Now, this is not to say that ALL LLI are clinically insignificant, just the majority of cases. As stated earlier, the estimated average LLI is 5.2mm with a standard deviation of 4.1, so at any given time a human could be walking around with a LLI of between 1 and 9mm. This range likely does not matter and will also not be fixed over the long term. But, the higher the number, the greater the chances that the inequality will pose a risk for injury and the genesis of pain. Studies show that once the difference reaches near 20mm (around 3/4 of an inch) the difference becomes clinically significant. In these cases, clinical interventions such as orthotics become relevant and could potentially be a solution to issues the patient is dealing with. But until the difference becomes clinically significant, your LLI is likely normal and NOT the sole cause of your pain.

If you are interested in further reading on this topic here are a few sources that can get you started

- Prevalence of LLI: Knutson GA. Anatomic and functional leg-length inequality: a review and recommendation for clinical decision-making. Part I, anatomic leg-length inequality: prevalence, magnitude, effects and clinical significance. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13:11. Published 2005 Jul 20. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-13-11

- Biopsychosocial approach to LBP: Kikuchi S. New concept for backache: biopsychosocial pain syndrome. Eur Spine J. 2008;17 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):421-7.

- Use of manual therapy as a treatment protocol: Bishop MD, Torres-Cueco R, Gay CW, Lluch-Girbés E, Beneciuk JM, Bialosky JE. What effect can manual therapy have on a patient’s pain experience?. Pain Manag. 2015;5(6):455-64.

- Cook C. Immediate effects from manual therapy: much ado about nothing?. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19(1):3-4.